вик услугиâS ann o chionn fhada a bha e nam inntinn an sgeulachd seo a chur air mo bhlòg, ach tha mi gu math slaodach, a reir choltais. Sgriobh mi ann an 2004 e. Bhuannaich mi duais leis cuideachd â sgoilearachd gu cursa goirid aig Sabhal Mòr Ostaig â ann am Mòd puist ACGA. Ach tha mi aâ cur an-seo e air sgathâs gu bheil an sgeulachd inntinneach airson daoine aig a bheil uidh ann an eachdraidh nan GĂ idheal anns na StĂ itean Aonaichte. [English translation below]

Ann an Ăite Nach Eil na Ăite

le Rudy Ramsey

Rinn mi mòran rudan, na mo bheatha, a chur air bhioran mi â rudan mar cĂ r-rèiseadh, aerobatics, marathons, taekwon-do. De na tachartasan a bu mhotha a chuir air bhioran mi? Uill, mar as trice, cha bâe na rudan sin idir, ach na laithean samhach, nuair a gheibhinn a-mach piosan Ăšr de dhâfiosrachadh Ăšidheal mu dheidhinn mo shinnsearan. Sin rud a chuireas air bhioran mi gu fĂŹor! Innsidh mi dhuibh mu dheidhinn latha mar sin. âS e sgeulachd fhiòr a thâann mu dheidhinn mo shinnsearan fhĂŹn agus cĂ nain nan GĂ idheal.

Tha ceistean air bhith agam air aâ chuspair seo còrr air fichead bliadhna. Mu dheireadh thall, lorg mi na freagairtean. Agus seo tòimhseachan dhuibh. Fhuair mi na freagairtean nuair a bha mi ann an Ă ite nach eil na Ă ite, ann an Ă m nach eil againne. Caitâ an romh mi?

âS e fear-sloinntearachd a thâannam â rannsaiche eachdraidh theaghaichean, gu fĂŹor. Tha mòran shinnsearan agamsa a dhâimrich Ă Alba a dhâEireann a Tuath, a dhâfhuirich an-sin fad ginealach, agus a rinn eilthireachd gu Carolina a Tuath Ă s deidh sin. Sin slighe chumanta, air a bheil âAlbannaich-Ulaidhâ, âs docha, no âUlster Scotsâ âsa Bheurla co-dhiĂš. Tha mu choig sloinnidhean deug anns aâ chraobh-ghinealaich agam a rinn imrich âsan aon doigh.

Tha aon teaghlach a rinn imrich mar sin anns a bheil Ăšidh shonraichte agam, leis an t-sloinneadh âKeaheyâ âsna lĂ ithean seo, no âMacKeacheyâ no âMacGeachieâ anns an t-seann dĂšthaich o chionn fhada. Dhâimrich iad Ă Alba a dhâĂireann a Tuath ron aâ bhliadhna 1749. Tha fios agam air sin oir gun dârugadh an triuir mhac ann an Ăirinn a Tuath anns aâ bhliadhna sin, no anns na trĂŹ no ceithir bliadhna Ă s a dheidh. Tha amharas agam gun do dhâfhag iad Alba direach an dèidh Bliadhna Thearlaich, ach chan eil mi cinnteach fhathast.

Thainig iad a Charolina a Tuath, a reir aithris ann an 1767, ach ro Ă m Cogadh na Ceannairce co-dhiĂš. Dhâfhuirich iad cha mhòr 50 bliadhna ann am pairt albannach de Charolina a Tuath. Bha e daonnan aâ cur ionnadh orm an robh iad nan GĂ idheil, agus ma bha, saoil? Dè cho fad âsa mhair an cĂ nan aca? Ach cha do smaoinich mi gun lorgainn a leithid de dhâfhiosrachadh gu brath.

DhâfhĂ s an Ăšidh agam anns na ceistean seo na bu mhotha an dèidh dhomh fhĂŹn tòiseachadh air GĂ idhlig ionnsachadh, airson adhbharan nach robh ceangailte ri eachdraidh mo theaghlaich. A dhâaindeoin sin, cha dâfhuair mi na freagairtean gu luath.

Ach thainig, mu dheireadh thall, latha gu math sonraichte. Bha mi ann an Ă ite nach eil na Ă ite, ann an Ă m nach eil againne. Uill, bha mi air an eadar-lĂŹon, co-dhiu â nĂŹ a thâanns a h-uile h-Ă ite agus nach eil ann an Ă ite sam bith. Agus bha mi ann an Ă m fada, fada ro na laithean seo. Bha mi aâ leughadh eachdraidh seann eaglais a bhâann am Mississippi o chionn fhada. Agus âs ann an-sin a bha iad â mo shinnsearan agus mo fhreagairtean.

Seo an eachdraidh. Anns aâ bhliadhna 1816, dhâimrich na triuir brĂ ithrean Keahey Ă Carolina a Tuadh a Mhississippi. Cha bâurrainn dhaibh sin a dheanamh ron a-sin, air sgath âs gu robh slĂ inte an athar ro bhochd airson a leithid de thuras. Ach choachail an athair, agus an deidh Ăšine ghoirid, dhâfhalbh an teaghlach gu leir airson am fortan a shireadh anns an stĂ it Ăšir sin. Bha na brĂ ithrean nan seann bhodaich an-sin. Cha robh iad fhèin aâ fuireach ann an Alba riamh; chur iad seachad cha mhòr leth-cheud bliadhna anns an tĂŹr seo. Am bitheadh facal sam bith de GhĂ idhlig aca fhathast?

Uill, mar a thachair, stèidhich iad eaglais Ăšr ann am Mississippi â eaglais air an robh Philadelphus Presbyterian Church â ainm a bhâair seann eaglais ann an Carolina a Tuath, far an robh iad aâ fuireach. A-reir eachdraidh na h-eaglise Ăšr, chaidh a toiseachadh ann an taigh a bhâaig fear de mo shinnsearan. Agus bâe mo shinnsearan a bhâann an ochdnar dhen aon duine deug a stèidhich an eaglais.

Ach seo an rud as cudromaiche dhomhsa: Chaidh Gà idhlig na h-Alba a chleachdach ann an coinneamhan nan luchd-stèidheachaidh. Bha geà rr-chunntas nan coinneamhan sgriobhte ann an Gà idhlig. Thog iad sgoil Úr cuideachd, an dèidh bliadhna no dhà . Agus an-siud, ann an siorrachd Wayne ann am Mississippi, ann am fÏor thaobh a deas nan Stà itean Aonaichte, theagaisg iad a h-uile clas ann an Cà nan nan Gà idheal. Agus lean sin fad iomadh bliadhna, gus an tainig daoine Úr aig nach robh Gà idhlig idir chun na siorrachd sin.

Cha bâurrain dhomh aâ bhith air freagairt na bâfheĂ rr fhaighinn do mo ceistean â no sin mo bheachd fhĂŹn co-dhiu. Chan eil fhios âam fhathast am bidh pĂ ipearan riâm faighinn bho lĂ ithean trĂ th na h-eaglaise. Ma bhios, bidh cothrom agamsa GĂ idhlig a leughadh a bha air a sgriobhadh le mo shinnsearan fhĂŹn â sinnsearan a bhâanns na StĂ itean Aonaichte ron Ă m a bha a leithid ann. Ann an doigh, bha iadsan cuideachd ann an Ă ite nach robh na Ă ite â fhathast.

[Mar as Ă bhaist, cha cuiridh mi stuth dĂ -chananach na mo bhlòg GĂ idhlig, ach tha an dĂ thionndadh agam mar tha, agus is docha gum bitheadh an tionndadh âsa Bheurla cuideachail do fheudhainn.]

In a Place Thatâs Not a Place

by Rudy Ramsey

Iâve done many things in my life that I found exciting â things like sports-car racing, aerobatics, marathons, taekwon-do. Which events were the most exciting? Well, often, they werenât these things at all, but quiet days when I discovered new pieces of interesting information about my ancestors. Now thatâs exciting! Iâll tell you about a day like that. Itâs a true story about my own ancestors and the language of the Gaels.

I had questions on this subject for more than twenty years. At long last, I found the answers. And hereâs a riddle for you. I found the answers when I was in a place thatâs not a place, in a time thatâs not our own. Where was I?

Iâm a genealogist â a family historian, really. I have a lot of ancestors who immigrated from Scotland to Northern Ireland, lived there for a generation, and then emigrated to North Carolina. Itâs a common pattern, known as âUlster Scotsâ. I have perhaps 15 surnames in my ancestral tree with this immigration pattern.

Thereâs one family like this which has a special interest for me, with the surname âKeaheyâ these days, or âMacKeacheyâ or âMacGeachieâ in the old country long ago. They emigrated from Scotland to Northern Ireland before 1749. I know this because their three sons were born in Northern Ireland in that year, or the three or four years thereafter. I suspect that they left Scotland after the Jacobite Rebellion, but Iâm not yet certain.

They came to North Carolina, reportedly in 1767, but in any case before the American Revolution. They lived nearly 50 years in a Scottish part of North Carolina. I always wondered whether they were GĂ idhlig speakers, and if they were, I wondered how long they retained the language in America. But I didnât think I would ever find such information.

My interest in these questions increased after I started learning GĂ idhlig myself, for reasons unrelated to family history. Even so, I didnât find the answers quickly.

But there came, at long last, a very special day. I was in a place thatâs not a place, in a time thatâs not our own. Well, I was on the internet, anyway â a thing thatâs everywhere and nowhere at all. And I was in a time far, far away from the present. I was reading the history of an old church that was in Mississippi long ago. And there they were â my ancestors and my answers.

Hereâs the history. In the year 1816, the three sons emigrated from North Carolina to Mississippi. This wasnât possible for them before then, because their fatherâs health was too poor for such a trip. But their father died, and after a short while, the whole family left to seek their fortune in the new state. The sons were old men by then. They themselves had never lived in Scotland; they had spent nearly half a century in this country; would there have been any trace of GĂ idhlig still with them?

Well, as it happened, they formed a new church in Mississippi â a church called the Philadelphus Presbyterian Church, the name of an old church in North Carolina, where they had lived. According to the history of the new church, it was created in the house of one of my ancestors. And eight of the eleven founding members were my own ancestors.

But hereâs the most important thing to me: Scottish Gaelic was used in the foundersâ meetings. The minutes of the meetings were written in GĂ idhlig. They built a new school, too, after a year or two. And there, in Wayne County, in Mississippi, in the true deep south of the United States, every class was taught in the language of the Gaels. And that remained true for several years, until new people came to the area who spoke no GĂ idhlig at all.

A better answer to my questions would not be possible â or thatâs my opinion, anyway. I donât know yet whether there are papers still surviving from the early days of the church. If so, Iâll have an opportunity to read GĂ idhlig written by my own ancestors â ancestors who were in the United States before there was such a place. In a way, they, too, were in a place that wasnât a place â yet.

Posted 11 years, 11 months ago at 11:14 pm. Add a comment

[This article is reprinted from my Ramsey-Farrell Family History Newsletter of November, 2003. A recent trip to Kennesaw Mountain has motivated me to post this article in the blog. In any case, future such articles will almost surely be posted here, rather than printed as a hardcopy newsletter. We've actually made a little further progress iin learning about William and Sarah Ramsey, but I'll tell you about that separately when we have it sorted out a bit more.]

A Good Day in the Life of a Genealogist

In the early 1990s, I had a professional conference in Atlanta, Georgia. For many years, I had hoped to find an opportunity to go there, because my G-Grandfather John Cannon Ramsey was born there. This was before the days of genealogy on the internet, and it seemed that my best way of finding his (then unknown) parents was to actually go and do research there in Atlanta.

John Cannon Ramsey

I was aware of an interesting family tradition about John Cannon Ramsey’s name. He is said to have been born in Atlanta during the siege of Atlanta, as Sherman did his famous march to the sea, destroying Confederate installations (and much else) that lay in his path. During his birth, the Ramseys could hear Sherman’s cannon fire in the distance, and so they named their son “John Cannon”. The problem with this story was that Sherman’s siege of Atlanta took place a month after the birth date I had for John Cannon Ramsey, and I always wondered if this story was one of those family myths, a nice story that would prove false in the end. Or, more likely, I had an incorrect birth date.

My conference ended on Friday, and the vital records office was closed until Monday, so I spent the weekend in the public library genealogy department. I probably spent 12-15 hours there, and didn’t find a thing. Once, when I was bored, I got up and walked around. I spotted a huge book on top of a filing cabinet, and looked to see what it was. It was a book of Civil War maps. I turned to the map of the siege of Atlanta. One thing that interested me was that Sherman’s march, which I’ve always thought of as a “blitzkrieg”, was quite a bit slower than I expected. Otherwise, I didn’t learn much from the map, either.

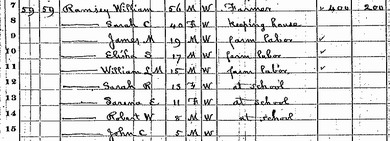

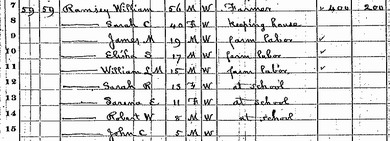

I had two days available to work at the vital records department, and I searched diligently through the records for Atlanta and the surrounding territory for our ancestors. With about two hours remaining, it was clearly time to try a new approach. I thought of the map, and realized for the first time that I might have the date (and the story) right, and the place wrong. I looked where Sherman was the month before Atlanta, and found them within a few minutes. They were some 35 miles north of Atlanta (blitzkriegs were slower in those days  ), in the Wildcat District of Cherokee County, Georgia. Here’s their 1870 census record (I also found them there in 1860).

), in the Wildcat District of Cherokee County, Georgia. Here’s their 1870 census record (I also found them there in 1860).

In addition to William and Sarah C. Brown Ramsey, you can see James Manley (“Manley”), Elisha S. (“Lish”), William Lawrence, Sarah Ruth, Sarena Elizabeth (“Betty”), Robert Wylie (“Wylie”), and our John Cannon.

The 1860 and 1870 census records here are the earliest traces I’ve found of our Ramseys [no longer true], but I’m still looking. William was born in North Carolina, and Sarah C. Brown was born in North Carolina or possibly South Carolina. I haven’t found further records of them in any of these places yet. There’s one more hint that will help, and I’ll discuss it below, but first let’s talk about cannons.

So What About the Cannons?

Here’s a segment of a wonderful map showing Sherman’s path through northern Georgia. I’ve highlighted Cherokee County, and marked the Wildcat District. I hope to use land records, or details of the census records, to locate the Ramseys more exactly, but haven’t been able to do this yet [this is also no longer true; we've found the land records, and the family farm was right at the south edge of the Wildcat District].

(Used with the kind permission of David Mastovich;

original larger map is here)

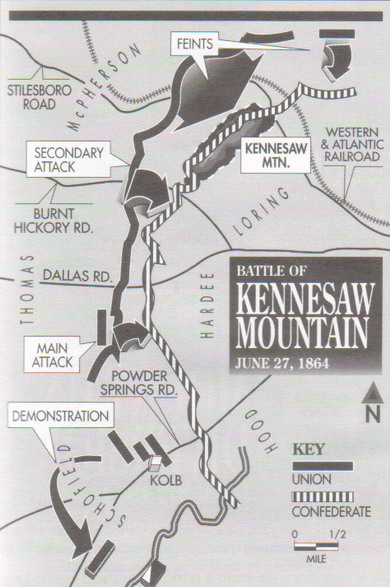

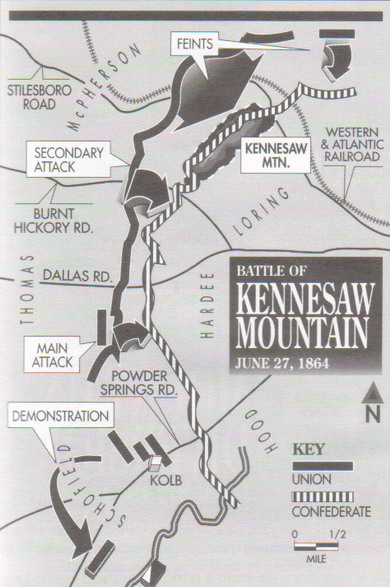

Although Sherman burned about half the town of Canton in response to a series of guerilla raids, there were no actual battles in Cherokee County. It seems highly likely that the cannon fire was associated with the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain, which stretched over the last half of June, and took place about 11 miles south of the Wildcat District. A three-day-long artillery barrage took place 19-21 June, 1864, and the fiercest fighting and largest artillery barrage, took place on 27 June 1864. I’m betting that if we ever learn John Cannon’s actual birthday, he’ll have been born on one of those four days. It’s interesting that his birth month brought us (correctly) to the place he was born, and the events that occurred in that place now suggest when he might have been born.

The Battle of Kennesaw Mountain

An army travels on its stomach, and Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman‘s greatest challenge as he invaded the southlands was to maintain an open supply route. His strategy was to follow the path of the Western & Atlantic railroad from Chattanooga down through Atlanta, rebuilding and defending the railway behind him. Keeping the railroad working all the way to his supply base at Louisville would be ideal, but he had also established huge storage facilities at Nashville, which might suffice in a pinch. Naturally, the Confederates were interested in preventing him from advancing on the rail route, and they would destroy the railroad both ahead of him and behind him to the extent they were able to do so.

Gen. Joseph E. Johnston‘s Confederate forces were outnumbered two to one, and couldn’t afford a pitched battle in neutral terrain. Trickery wasn’t working for them, either. Johnston’s neat trap at Cassville was foiled when a small group of lost Union cavalry happened to spot them, and sounded the alarm. And Sherman’s intimate knowledge of northern Georgia allowed him to sidestep an ambush at Altoona Pass. And for the rest of the six weeks since the start of the Atlanta Campaign, Sherman’s flanking maneuvers had forced Johnston to gradually retreat eighty of the hundred miles’ distance down the railroad from Chatanooga to Atlanta. Even Johnston’s defensive victories at New Hope Church and Pickett’s Mill had been more costly, percentagewise, to the Confederates than to the Union forces.

But with the retreat to Kennesaw Mountain on June 15, 1864, Johnston finally found himself in a truly defensible position. Standing to a height of 700 feet and more than two miles long, the twin peaks of Kennesaw provided substantial natural fortification, and lots of opportunity for man-made trenches, entanglements, and sharpshooter positions. The side facing the Union forces is steep and rocky, while more gentle slopes on the southeast side allowed ready access for the rebel forces. Swollen creeks had created swampland just in front of both ends of the 6-mile arc of defensive entrenchments built by the Confederates, providing protection against a flanking attack. With the railroad running just past its east end, Kennesaw Mountain was a perfect defensive position. It seemed impregnable.

As a preparatory step while reconnoitering the position, Sherman launched an artillery barrage on the fortifications of the mountain. This barrage involved 130 cannon, and continued nonstop for three days, on June 19, 20, and 21. Sherman, his troops said, was determined to either take the mountain or “fill it full of old iron”. This certainly could be the cannon fire that our Ramseys heard, though there was an even greater barrage later, as we’ll see.

Sherman side-stepped his entire army to the right, and his generals Hooker and Schofield advanced their forces in a flanking attempt. Johnston had prepared for this possibility by moving Gen. Hood’s Army Corps from the right end to the left end. The ever-aggressive Hood attacked the entrenched Union forces at Kolb’s Farm, but couldn’t break through, and lost 1000 men to Sherman’s 350. In failing to pursue, however, the northerners gave Hood’s forces time to set up their own entrenchments. That effectively stopped further flanking attempts by Sherman, unless he was willing to over-stretch his forces and leave his supply line quite vulnerable.

Map of the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain (reprinted from Dennis Kelly’s excellent book, “Kennesaw Mountain and the Atlanta Campaign: A Tour Guide”, with permission; full reference below)

Sherman now found himself considering the reverse of his usual flanking attacks. He felt that by holding on the flanks and attacking the obviously-strong center, he might achieve sufficient surprise to succeed, and might in any case correct a laxness that was beginning to set in with his own troops after six weeks of flanking and feinting with relatively little serious fighting. He gave his field commanders two days to prepare, while withholding knowledge of the battle plan even from their own staffs.

On June 26, the day before the planned battle, Schofield’s troops at the south end of the eight-mile-long front demonstrated loudly, and feigned preparations for an attack, hoping to induce Johnston to move troops there and weaken his center. He didn’t take the bait.

For 15 minutes, starting at 8:00 AM, June 27, 1864, the whole of the Union army’s artillery (some 250 cannons) laid down a barrage, especially on Big Kennesaw and Little Kennesaw and the little spur now called Pigeon Hill at the south end of the mountain.

The print above (Louis Prang, 1880s) shows a part of the huge artillery barrage Sherman laid down against the Confederate forces holding Kennesaw Mountain on the morning of June 27, 1864. (Modern reprints of this image can be obtained here.)

When the cannon fire stopped at 8:15, Union forces launched a feint attack on Big Kennesaw (the eastern end of Kennesaw Mountain, by the railroad) and two seriously intended attacks at Pigeon Hill and at Cheatham Hill, farther to the south. These attacks incurred heavy Union losses (Sherman estimated 3000), while doing little damage to the enemy, and without dislodging the Confederates. The battle was clearly a victory for Johnston.

But ironically, Johnston and his commanders were sufficiently distracted by the heavy Union assault that they failed to pay adequate attention to Schofield’s feigned attack at the south end of the battle front. There, Gen. Jacob D. Cox alertly and skillfully took advantage of the situation, and made inroads into the Confederate defenses that were to provide the basis for Sherman’s next move, another flanking movement to the south end of the line. This forced Johnston to abandon his position on Kennesaw Mountain on July 2, and retreat several more miles toward Atlanta.

Our little history is now so close to a critical turning point in the war that I think I’ll go ahead and tell the story, even though it has nothing directly to do with Kennesaw Mountain or the Ramseys. Johnston was a very skillful strategist whose ability to delay Sherman for eight weeks while gradually conducting an orderly retreat to Atlanta was a significant success. Atlanta really was impregnable. By mid-July, Johnston was in Atlanta, surrounded by the now badly stretched-out forces of Sherman. On the eastern front, Lee was barricaded into a similar fortress at Petersburg, with the result that the entire Civil War was in a stalemate. If the South had been able to maintain this situation until the coming federal presidential election, it’s likely that Lincoln would have lost the presidency to a concession-minded candidate. Had that happened, the United States would not now exist. Only a miracle could prevent this.

The miracle came when Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederacy, stupidly removed Joseph Johnston from command, and promoted Hood in his place. Hood immediately started attacking everything in sight. Indeed, his tendency to attack at every opportunity converted a defensible position to an eventual loss, and Sherman held Atlanta, and effectively Georgia, by September 2. This so raised northern spirits that Lincoln won re-election in a landslide, and continued the war to the end.

The Ramsey Family Plot at Marysville

But it’s time to return to family history. It’s easy enough to work forward in the Ramsey family. Between 1870 and 1880, they moved to Cooke Co., Texas, where they lived in Marysville. But working backward in time has proven difficult. Both William and Sarah have relatively common names, and it’s hard to trace them without knowing anything further about their birthdates, birthplaces, date or place of marriage, etc.

The situation changed earlier this year, though. While searching the internet for more information about William and Sarah, I came across a tombstone survey of the Marysville Cemetery. There they were, although there was some confusing information. Sarah was listed twice, with conflicting information — a vestige of an old DAR survey, as it turns out. I sent an e-mail message to Barbara Jarvis to thank her for the survey and ask about the discrepancy. Since she indicated on the website that they were going to resurvey this cemetery sometime later in the year, I said I hoped they would take photos of the Ramsey graves, as they had done for some of the other graves there.

The next day, she and her husband went out to the cemetery, took seven photos of the Ramsey plot there and sent them to me. They also resolved the discrepancy. The plot is a fenced-in area with several graves, including William and Sarah, their children William Lawrence, Sarah Ruth, and Sarena Elizabeth, as well as Sarah Ruth’s husband, W.A. Whittington.

The most exciting thing, though, was the amount of detail on the tombstone of William and Sarah. As you can see below, it shows birth and death dates for both, as well as their marriage date. It’s a rare tombstone that contains this much historical information.

Although I still haven’t found them before the 1860 census in Cherokee County, Georgia, we’re now armed with information that should help us recognize them when we do. There’s a lot that I haven’t done yet to try to find them, and I’m now hopeful indeed. I’ll keep you posted. Maybe we’ll even get lucky and one of the readers of this newsletter will have information that will help.

Sources for More Information

For more information about the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain:

For Cherokee County, Georgia:

- Cherokee County, Georgia Genealogy

- Rootsweb, Cherokee Co., Georgia

- USGenWeb Archives, Cherokee Co., Georgia

- Cyndi’s List, Cherokee Co., Georgia

- Historical Atlas, Cherokee County, Georgia

- Map, Cherokee County, Georgia, 1864

- Cherokee County Historical Society

- Northwest Georgia Historical and Genealogical Society

- Rev. Lloyd G. Marlin, “The History of Cherokee County”. Atlanta: Walter W. Brown, 1932 (1997 reprint can be obtained from CCHS, above)

For Cooke County, Texas:

Posted 17 years, 3 months ago at 10:32 am. Add a comment